Lessons from Midrash on Torah Portion of Noah

by the Executive Director of Ask Noah International

Delivered as a talk at the 4th International Noahide Conference, Jerusalem, Israel, 5779 (20’19).

We begin with a disclaimer on the subject of taking lessons from Midrash. The Midrash generally encompasses the stories that were passed down in the Torah tradition about the persons and events in the Hebrew Bible (Tanach). These stories are part of the Oral Torah, and they contain deep hidden meanings that were intended specifically for the Jewish people, which inherently makes them a type of in-depth Torah study. In general, their relevance to Noahides is limited to the parts that the classical clarifiers of the Tanach, such as Rashi, quoted as needed for the purpose of explaining the straightforward meanings of the Bible verses.

The exceptions, as explained by Rabbi Moshe Weiner in The Divine Code, Part I, ch. 5, are the Midrashim on the first two weekly portions of the Torah, Genesis and Noah, because they deal with periods of Biblical history that have messages that are relevant for all humanity.

Therefore, that part of the Midrash is relevant for Noahides to learn, and this essay will examine some selected Midrashim on the Torah portion of Noah.

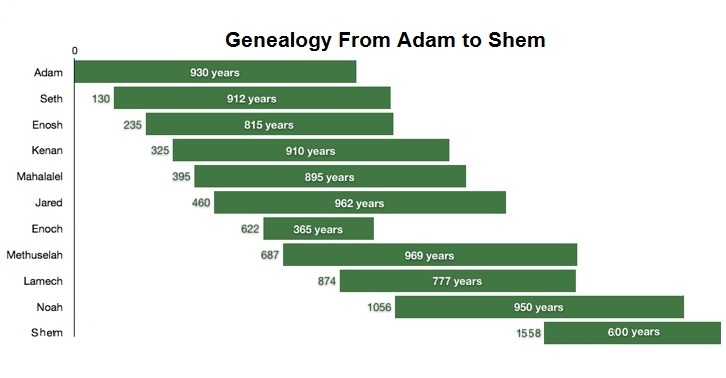

The death of Methuselah

We will begin with the day on which Noah finished his construction of the ark. That day was his 600th birthday. From the words that G-d spoke to him, his understanding was that the rains of the Flood would start on that day. He had warned the population that they only had until that day to repent, before the Flood would come. The day came, but there was no flood, so the people started laughing at Noah even more than before.

But they didn’t continue their laughing for very long, because on that day, Methuselah died at the age of 969. He was the person whom the people of that generation revered as being the most righteous in their eyes. He had studied from Adam, the first man, for 243 years. So when he died, everyone started their traditional period of seven days of mourning when a loved one passes away.

At that point, G-d told Noah in Gen. 7:4 that the Flood would come at the end of another seven days. G-d delayed the Flood to give the people time to complete their seven days of mourning for Methuselah. Since a period of mourning is a time for the mourners to be introspective about their own lives and to do repentance and better their ways, that was a final chance for the people to repent from their sins. If they would repent, G-d would rescind His decree to bring a flood over the entire world. The people did not repent, but this episode holds a lot of teachings for us.

This is a source for the Torah Law that Jews should observe a seven-day period of ritual mourning when a close relative passes away. It’s called “sitting shiva” for short, which means “sitting sheva yamim” – sitting (in mourning) for seven days. But the death of Methuselah happened long before the Torah was given to the Jews. The Lubavitcher Rebbe says that this proves that the concept of a seven-day mourning period, along with more of the details in the Jewish tradition for mourning, apply to Non-Jews as well. In one of his talks, the Rebbe explained the following [1]:

There are matters in Torah which belong in the category of “creating a settled world”. These matters existed before the giving of the Torah. Therefore it is understood that these matters apply also to the Children of Noah, even though they aren’t stated explicitly in the part of Torah that speaks about the Seven Noahide Laws. The explanation and proof of this is that if something is logically intuitive to mankind, about whom the Mishna of Ethics of the Fathers also says, “Man is precious, for he is created in G-d’s image,” that is a sign that the subject has a logically required connection to Gentiles, especially if it falls in the category of “creating a settled world.”

This applies to the subject of mourning, as Rambam writes that, “Anyone who does not mourn as the Sages commanded is insensitive.” On the other hand, Rambam continues and writes that, “A person should not feel hurt over the deceased too long, for this is the way of the world, and one who pains himself more than the way of the world is a fool. How should he act? The first three days for weeping; a total of seven for mourning [and continuing to receive comfort from visitors], a total of thirty days before cutting the hair, and so on;” referring to all the other aspects of traditional Jewish mourning that extend past then until twelve months [which are mainly for those who lose a parent, G-d forbid].

But afterwards, G-d made it [human] nature that “the the pain of the loss dissipates and most of the time is not felt.] Therefore, since these matters are connected with the way of the world and its being made into a settled environment – it’s logical that they apply to the Children of Noah as well: on one hand the imperative to observe a period of mourning and not to be insensitive, and on the other hand, the prohibition not to mourn too much or too long.

Now getting back to our story about Noah, that’s an important teaching, but what about the fact that G-d had indicated to Noah that the punishment of that generation would begin on a certain day, but instead it started seven days later? The Maharal of Prague explains that the sadness that everyone felt during the seven days of mourning for Methuselah was actually the beginning part of the pain that would be brought on them by the Flood. So the date of the beginning of their punishment was really not postponed.

The gathering of animals into the ark

It was on the seventh day that the pairs of animals and birds from all over the world began arriving at the ark: one pair each of the species that are not tahor (not ritually “pure,” such that Jews would be forbidden to consume them in the future), and seven pairs each of the species that are tahor [2]. When the people saw that the animals were coming from all over the world, which could only mean that it was inspired by G-d, that’s when they finally started to get worried. Has there been any other time in history when a miracle like this happened? In fact, yes.

Leviticus ch. 11 gives the Torah Laws about which creatures are tahor (ritually pure) for Jewish consumption, and which are not. In verse 2, G-d tells Moses, “Speak to the Children of Israel, saying, ‘These are the creatures that you may eat from among all the animals that are upon the earth.” Rashi explains, based on Talmud, that Moses held up each type of creature – each type of animal, bird, and creeping thing that is mentioned there by name – and showed it to the Israelites.

Moses pointed and said, “this kind you may eat,” and “this kind you many not eat.” One of each of all those types of creatures came on its own, as inspired by G-d, to Moses at Mount Sinai at that time, just as the animals came to Noah’s ark 17 generations earlier.

Noah’s reluctance to enter the ark

When the downpour started, Noah finished getting all the animals and his family into the ark, and G-d told him to go into the ark as well. But he didn’t go in. He stood outside in the rain until G-d forcibly ordered him to go into the ark. Some of the Sage say that this shows that Noah didn’t really have faith that G-d would bring the worldwide destruction. What is meant is that he didn’t believe that the Flood would come. How is that possible?

It means that he didn’t think that G-d would bring the Flood while he was still outside the ark. So he deliberately stayed outside, to try to delay the Flood. Even if it was only for another minute, or a few minutes, he was giving the people the chance of a little more time to repent and save themselves. In other words, after all the open miracles (and we’ve only mentioned a few), and with the rain coming down, he couldn’t believe that the people would refuse to repent. And maybe G-d Who is good would find some tiny merit in the people at the last minute, by which they could be spared.

Even if they wouldn’t repent, or no redeeming good could be found, Noah didn’t believe that G-d would bring the Flood while he was still outside the ark, so he was staying outside because he didn’t want to be responsible for mankind’s destruction, on account of him shutting himself up in the safety of the ark. But G-d knew that the people would refuse to repent, and that the world had to be cleansed from that evil. So G-d ordered Noah to go inside, and He shut and sealed the door of the ark.

What is the bottom line about this? Although Noah had all of those good intentions, nevertheless, he should have submitted to G-d’s instructions immediately, as soon as G-d told him to go into the ark. He shouldn’t have thought that it was up to him to decide when he would enter [3].

Noah’s dove and the olive leaf

Let us now skip to a famous scene: the return of the dove after it was sent out a second time by Noah. In Genesis 8:11, the dove came back to him in the evening, and behold, an olive leaf it had plucked with its bill. Rashi and Ramban explain that the dove was communicating the following message to Noah: “I prefer to sustain myself with food as bitter as an olive through G-d’s direct kindness, rather than through foods sweet as honey that I would receive from relying on a human being.”

There is wisdom in this message: It’s better to live one’s life through honest hard work, while having faith in G-d that you’ll succeed, than to get greater wealth by putting your faith in people instead of in G-d.

But there was also something negative about this. It was very disrespectful for the dove to present that message right to Noah’s face, after it had survived for a whole year only due to the kindness and self-sacrifice that Noah expended to bring it food to keep it alive. A person should always make a point of thanking someone who does something good for him.

In the Midrash Genesis Rabbah 33:6, it says that Noah scolded the dove for damaging the olive tree that was so much needed after the devastating Flood. This parallels an account written by the Previous Lubavitcher Rebbe about something that happened when he was 16 years old, while he was taking a walk with his father, the fifth Rebbe. The Previous Rebbe writes [4]:

It was the summer of 1896, and Father and I were strolling in the fields of Balivka, a hamlet near Lubavitch… Said Father to me: “See G-dliness! Every movement of each stalk and grass was included in G-d’s primordial thought of creation, in G-d’s all-embracing vision of history, and is guided by Divine Providence toward a G-dly purpose.” Walking, we entered the forest. Engrossed in what I had heard, excited by the gentleness and seriousness of Father’s words, I absentmindedly tore a leaf off a passing tree. Holding it a while in my hands, I continued my thoughtful pacing, occasionally tearing small pieces of leaf and casting them to the winds.

“The Holy Ari [Rabbi Yitzchak Luria],” said Father to me, “says that not only is every leaf on a tree a creation invested with Divine life, created for a specific purpose within G-d’s intent in creation, but also that within each and every leaf there is a spark of a soul that has descended to earth to find its correction [tikkun] and fulfillment. Talmud… rules that ‘a person is always responsible for his actions, whether awake or asleep.’ The difference between wakefulness and sleep is in the inner faculties of a person, his intellect and emotions.”

“The external faculties [these are the bodily organs] function equally well in sleep; only the inner faculties are confused [these are the faculties of thought and intellect]. So, dreams present us with contradictory truths. A waking person sees the real world; a sleeping person does not. This is the deeper significance of wakefulness and sleep: when one is awake one sees Divinity; when asleep, one does not. Nevertheless, our Sages maintain that a person is always responsible for his actions, whether awake or asleep.”

“Only this moment we have spoken of Divine Providence, and unthinkingly you tore off a leaf, played with it in your hands, twisting and squashing and tearing it to pieces, throwing it in all directions. How can one be so callous towards a creation of G-d? This leaf was created by the Al-mighty towards a specific purpose, and is imbued with a Divine life-force. It has a body, and it has its life. In what way is the ‘I’ of this leaf inferior to yours?”

Is there still a possibility of finding Noah’s ark?

Let us turn now to a famous question: Where is Noah’s ark? Is it still extant? In the story of Purim, in the Book of Esther, Haman obtained a beam that was 50-cubits long to use as the gallows from which he would hang Mordechai the Jew. But miraculously, the situation was reversed, and Haman was hung from that beam. According to the Midrash, Haman’s beam was from Noah’s ark.

At the end of II Kings 19, it relates that during the reign of King Hezekiah over the nation of Judah, King Sancheriv of Assyria laid siege against Jerusalem with an overwhelming army of 185,000 soldiers. Hezekiah prayed to G-d with full faith, and that night an angel killed the entire army, except for King Sancherev. Sancherev fled to the temple of his idol, where he was assassinated by his two of his sons. The Talmud relates that his idol was a beam from Noah’s ark.

King Sancheriv and Haman [5] were exceedingly rich people. So we can presume that whole beams from Noah’s ark were highly valued collector’s items, which people with their level of wealth could afford. Therefore there is good reason to doubt whether there is really any of Noah’s ark left on Mount Ararat.

The commands to Noah about the 7 Laws, and forbidding any ritual of Sabbath rest

When Noah exited the ark, G-d said to him (Gen. 8:22), “Continuously, all the days of the earth, seedtime and harvest, cold and heat, summer and winter, and day and night, lo yishbosu.” The Hebrew words “lo yishbosu” at the end are intended to communicate two meanings. One meaning is “they will not cease” – although the seasons stopped functioning during the year that the Flood lasted, from that time on they won’t stop from following their normal pattern.

It also means “don’t make a Sabbath.” In Tractate Sanhedrin, the sage Reish Lakish says that this was a command to the Children of Noah that they are forbidden to keep a ritual Sabbath. Rashi clarifies that this command was given as a prohibition directly for Noah himself, who righteously followed the Seven Commandments, and for his whole family, and for all his descendants that would come from him (with the exception of the Jewish people, who were commanded differently after G-d miraculously brought them out of slavery in the Exodus from Egypt).

Rabbi Yehudah the Prince then explains there in the Talmud that this applies for any day of the week. Therefore Rambam brings this in Laws of Kings, ch. 10, as part of the Noahide Code.

Then Genesis ch. 9 starts out with the verses in which G-d gives explicit prohibitions of eating the meat of a living animal, and murder (including suicide and abortion), and to establish courts of Law. Then starting with verses 9:9-17, the rainbow with seven colors is shown to Noah, and G-d states the word “Covenant” to Noah seven times. G-d promised it is eternal, to let us know that there are seven eternal Divine commandments for the Children of Noah. (The other four commandments are referred to in other places in the Torah.)

Noah’s error of indulging in wine

After Noah stepped out into a barren world, he decided to start doing what he did best: working on agriculture to grow crops for sustaining the new population. The Midrash says that it’s at that point that the accusing angel, Satahn, stepped in. He appeared to Noah and started trying to convince him to wait on the food crops, and attend first and foremost to planting a vineyard and making wine. The Satahn made sure that those grapes grew miraculously quickly, and they were miraculously tasty, and they made miraculously good wine. This was a spiritual test for Noah. He didn’t pass the test, and not-good consequences came from that.

What this teaches and warns us is that it’s wonderful to be involved in doing good deeds, but when a person gets drawn into doing it in the particular way that’s also what he wants to do most of all, and it’s what he enjoys doing the most, then alarm bells should start going off in the person’s head. Is this the particular good deed that G-d wants him to be doing now? Or is he doing it in the way that G-d wants? Is he doing it for the sake of Heaven? Or is it becoming all about him?

If the last one is the case, the person may wake up one day and realize that G-d wanted and needed him to do something else with his time and energy, and maybe now it’s too late, because the opportunity is lost. A person needs to always try to keep this in mind.

Nimrod’s strategy for rebellion against G-d

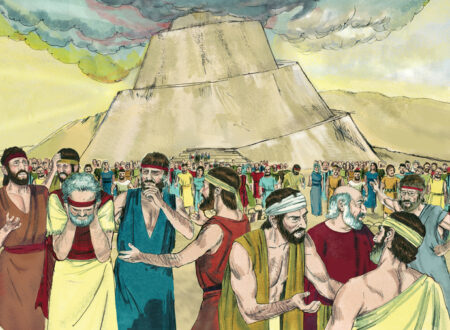

Now we go to the rebellion of Nimrod against G-d. Nimrod was a genius in engineering, architecture, urban development, military strategy, public speaking, and propaganda. He attracted people to follow him by using his strong personality, his prestige, his charm, and by professing that he had the best intentions and dedication to fairness for everyone. By the age of 40, he saw that the people were ready for him to declare himself to be their king and their god, and to convince them to worship him.

Nimrod knew about G-d, and that He had cleansed the world from a generation of hopelessly sinful people by sending the Flood. So he set out to rebel against G-d in a way that he thought would sidestep the specific sins that sealed the decree of the Flood. He knew that G-d brought the Flood on account of all the people seeking to harm each other, and that G-d has more patience for sin when there is unity and brotherly love among the sinners.

Therefore, Nimrod’s plan was to unify everyone in peace and brotherhood, in conjunction with rebellion against G-d, for he thought that G-d would then be more patient and forgiving. Nimrod’s purpose in building the Tower of Babel was to unify everyone around it, including in a rebellion against G-d and against the Seven Commandments that G-d gave through Noah.

Only a few people didn’t join Nimrod’s rebellion. These were Noah, Shem, Eber, Abraham, and Ashur the son of Shem. What were their responses to the tower? Noah removed himself and concentrated on agriculture. Shem and Eber left and established a small academy for learning Torah. Ashur left and founded the city of Nineveh in G-d’s honor. Only Abraham stayed, and he constantly spoke out publicly against Nimrod’s evil rebellion and idolatry.

The 70 Biblical nations of mankind

When G-d finally put a stop to the Tower of Babel, He punished the people by confusing their communications with 70 different languages for the 70 families of mankind. Although the people at that time were organized into 70 national groups, they had been living in unity, with a common language of Biblical Hebrew. Because they took advantage of their unity by relying on it to achieve success in their rebellion against G-d, He broke up that unity by dividing them with different languages.

G-d also sent destruction against the people and their tower. Tur on Gen. 11:8 says that G-d sent a massive storm of hail onto the people. Genesis Rabbah 38:10 says that G-d sent a tidal wave in from the sea that drowned almost half of the population. It says that 30 of the 70 national families were wiped out, and those were eventually replaced by the 30 nations that arose later from the descendants of Abraham: these were sixteen nations from the children of Keturah, 12 from Ishmael, and two from Jacob and Esau – the Israelites and the Edomites.

This points out a mistake that can be found on-line. Some people have the idea to take a world map, and match up the people from the cultures of the modern-day countries with the names of the 70 Biblical families that are listed in Genesis as the families that arose after the Flood, before the Tower of Babel. But the Midrash relates that 30 of those families didn’t survive when the tower was destroyed. We just aren’t told which of the original 30 national families were wiped out. And as the saying goes, the rest is history…

Footnotes:

[1] This talk is quoted and referenced on our web page https://asknoah.org/faq/torah-perspective-on-mourning

[2] See Rashi on Gen. 7:2. From here we see that a Gentile should choose tahor species of animals if he makes sacrificial offerings to G-d. See The Divine Code, Part I, ch. 7.

[3] Besides the fish, there was only one being that survived the flood outside the ark. That was the giant Og. He eventually became the king of Bashan many generations later, until that nation to the east of the Golan Heights was conquered by Moses and the Israelites. Genesis 7:23 says that “only Noah [in Hebrew, ach Noach] survived, and those with him in the ark.” But in Hebrew, the phrase ach Noach has the numerical value (gematria) of 79, which is the same as the numerical value of the name “Og.” So the survival of Og is hinted to in that verse.

[4] From the writings of the sixth Lubavitcher rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn; translation/adaptation by Yanki Tauber. Presented here from the web page https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/66990/jewish/The-Leaf.htm

[5] See Esther 3:9.